Oliver Balch speaks to Holcim’s head of sustainability about the Swiss construction giant's efforts to shift to greener alternatives in its quest to becoming net zero by 2050

It would be difficult, if not impossible, to picture the modern world without cement. This durable, multipurpose ingredient of concrete provides the literal building blocks of our constructed environment – from dams and roads to buildings and bridges..

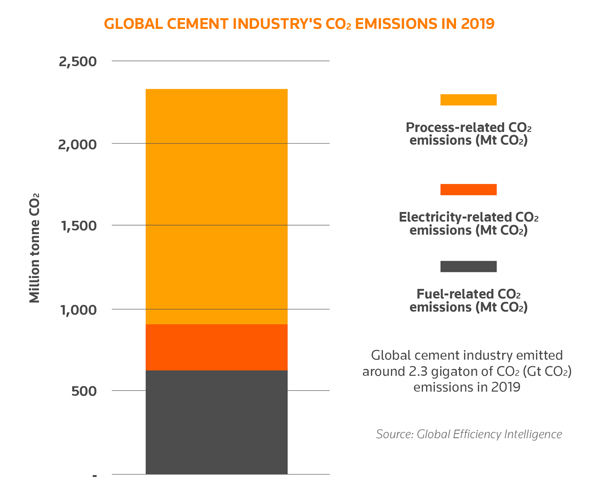

Yet, such omnipresence comes at a cost. With an estimated annual footprint of 2.6 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide, (estimated at between 4-8% of global emissions) cement would be the fourth largest emitter were it a country (behind the United States, China, and India).

Magali Anderson is the French-born head of sustainability at Holcim, the world’s largest manufacturer of building materials. By her reckoning, two billion people are set to move to cities over the next three decades. Accommodating them all will require room to be made for an urban area the size of New York every single month. That’s a lot of cement (as well as other aggregates that go into making concrete).

If there were a more eco-friendly alternative material with the same longevity, fire-resistance, cost effectiveness and cooling properties, then the conversation could end there. Unfortunately, there’s not.

Without the option at present to switch to a sustainable alternative, the rational response is to de-link urban growth and infrastructure expansion from concrete-related emissions.

So argues Anderson, who joined Holcim back in October 2016: “It’s a duty for our industry to decarbonise concrete because concrete is needed for society … I mean, I would challenge you to build a wooden dam [or] a 60-metre high-rise building without concrete.”

A wooden dam does indeed sound challenging but decarbonising the cement sector is certainly no walk in the park, either.

Holcim has set itself the goal or reducing emissions of ‘cement-like material’ from 561kg of CO2 per tonne in 2019 to 475kg by 2030

Holcim hasn’t made the challenge easier for itself. The Swiss-based multinational (formerly LafargeHolcim) has pledged to become net zero by 2050.

As part of that goal, it has set itself a host of exacting goals (endorsed by the Science Based Targets initiative) between now and 2030. The list includes a reduction of emissions of “cement-like material” from a benchmark 561kg of CO2 per tonne in 2019 to 475kg by 2030.

“At the end of the day, my job is to decarbonise the mass production of cement because that’s what the climate needs,” says Anderson, with the no-nonsense directness of the engineer that she is.

Holcim has two basic strategies for making this happen. The first focuses on making the industry’s traditional operations more energy-efficient and less polluting – a critical move given that operational emissions (i.e. scope 1) represent around 75% of Holcim’s total footprint.

In practice, this translates into a range of on-the-ground activities at its portfolio of 2,500 or so plants; from replacing fossil fuel for low-carbon alternatives and investing in waste-heat recovery, through to reducing levels of clinker (a carbon-intensive material used as a binder in cement) and cutting energy use where it can, among other measures.

“The good thing about these traditional levers is that we know them very well. [Now] it’s a question of pushing more on accelerating them compared to what we’ve been doing in the past,” says Anderson.

This tactic of slow but constant improvement has delivered a 28% reduction in carbon intensity of its cement manufacturing since 1990. Keep with the same plan, Anderson says, and the company should hit its 2030 targets without too many problems.

On the face of it, the tactic feels like a modest commitment to incremental improvement. Instead, what Holcim’s head of sustainability wants to avoid is the approach of the oil and gas industry (where she worked previously for 27 years): namely, failing to act seriously on climate in the hope a miraculous innovation will come along to save the day.

CCS is becoming a strong priority for everyone, which is why I’m convinced that by the time we need it in 2030, it will work

That said, Anderson concedes that incrementalism won’t get the cement sector to net zero in the long run. Incidentally, the same goes for investing in offsets and trusting in carbon pricing schemes (the cement sector has enjoyed free pollution permits for years under the European Trading Scheme, for example).

What will work, she says, are some seriously smart breakthroughs. Here, she has a front-row seat, balancing her sustainability role with responsibility for Holcim’s innovation division.

The two themes are closely interwoven, she insists, with the sustainability tag attached to around half of the company’s annual R&D budget (which totalled €142.5m in 2019) and about two-fifths of all its new patents.

At the operational level, Holcim’s post-2030 hopes are pinned closely to carbon capture and storage (CCS). Again, Anderson is eager not to over-egg advances here. At present, CCS technology is present in only a handful of cement plants worldwide, and then mostly at pilot scale (Holcim has five projects that Andersen would describe as “advanced”). (See also Is this breakthrough moment for carbon capture and storage?)

By the same token, she is confident that CCS will be a commercial proposition by the end of this decade. Not only does the essential technology already exist, she argues, but there’s also a collective effort to make CCS work beyond just the cement sector.

“It’s becoming a strong priority for everyone, which is why I’m convinced that by the time we need it in 2030, it will work,” she states.

Helping drive that process, she adds, is the growing number of government-backed incentive schemes supporting CCS. She cites the example of the European Commission’s €20bn Innovation Fund, which last year received 14 applications for large-scale CCS schemes in its first call-out for projects.

Where Anderson’s enthusiasm for innovation really gets going, however, is in the creation of green (or greener) products.

Concrete is a super old product and the true disruption in the way we build is definitely 3D printing

The company’s website names 28 green building solutions, from sustainable insulation foam for your attic to a permeable, rain-absorbent concrete that helps recharge aquifers and reduce the risk of flooding.

Among Anderson’s favourites is ECOPact, which combines low-emission raw materials and operational-level emission reductions to create a concrete with a carbon footprint 30% lower than standard.

Another exciting development, in her view, is 3D printing. Holcim was part of a team of innovators behind a “first of its kind” 3D concrete printed arched bridge in Venice. Unveiled for the city’s recent Architecture Biennale, the structure requires no reinforcement bars and was built in situ.

“We have been building the same way for thousands of years. Concrete is a super old product and the true disruption in the way we build is definitely 3D printing,” she argues.

Take the example of a low-income country like Malawi, where there is a 36,000 shortfall of classrooms. With a 3D printer, it’s possible to construct the walls for a school in 16 hours – all with less energy, less concrete, and lower transport-related impacts.

Holcim’s strategy of operational improvements, tech innovation, and greener products is a recipe for decarbonisation, but it won’t be enough for Holcim to hit its carbon neutrality goal in full.

For that, a system-wide transformation will be needed. There’s the 25% of emissions that lie outside its scope 1 remit, for starters. Its suite of green solutions will help here, but so too will public policy.

Anderson gives the example of “closed loop” solutions. For reasons of product safety, legislators are reticent to allow the re-use of construction demolition waste in concrete mixes. Switzerland is one of the few countries that does, although the total allowable content is capped at 20%.

We haven’t yet seen people saying, ‘Unless you give me a green product, then we won’t buy it’

Other policy disincentives include changes to the Emissions Trading System (under the EU’s new Fit for 55 package), which will mean that carbon that is captured and then re-used will no longer be eligible under the scheme.

“So if I capture my CO2 and I transform it into something useful for society, which is fantastic for circularity, then I'm not going to get the credit … am I incentivised to do it?” she asks (answer: “no”).

The lack of consumer-side pull is another major hurdle. Green cement typically costs considerably more than standard cement (double by some estimates). “We haven’t yet seen people saying, ‘Unless you give me a green product, then we won’t buy it.”

Again, progress is hindered by lack of incentives. At present, the more cement a company like Holcim sells, the higher its revenues. Its decision to launch a digital pavement design and sourcing tool that helps road builders use less concrete therefore appears noble, but financially naïve (at least from the perspective of short-term profitability).

This could change fast. Talk of government agencies requiring lifecycle impact information as part of public tenders (so-called ‘environmental public declarations’) is already on the up, for instance.

Perhaps the most encouraging sign at a systems level is the Global Cement and Concrete Association’s recent decision to launch a Concrete Action for Climate coalition. One of the stated aims of the initiative, which covers 40% of the cement industry, is to drive demand for low-carbon cement (Other goals focus on financing and public policy aspects of a net-zero transition).

Anderson also sees the industry’s main association as uniquely placed to position the sector as a whole. “We know that cement is a good product,” she says, “and we want to make sure everyone knows it could be a better product still.”

Oliver Balch is an independent journalist and writer, specialising on business’s role in society. He has been a regular contributor to The Ethical Corporation since 2004. He also writes for The

Guardian among other UK and international media. OIiver recently completed a PhD at Cambridge University, focusing on corporate ethics in foreign investment.

Holcim Net Zero concrete cement sustainable construction SBTi CCS 3D printing EU innovation fund ECOPact ETS Fit for 55 Concrete Action for Climate coalition